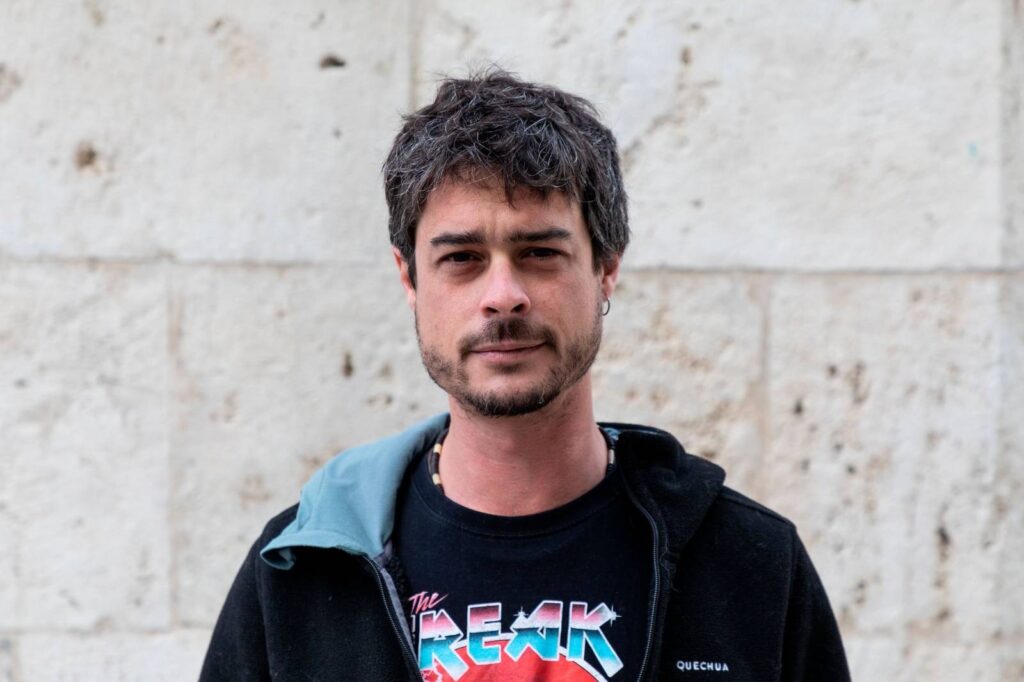

In this Q&A, Raffaele Angius from IrpiMedia talks with RFW’s Network & Development Lead, Peter Matjašič about an investigation that traced Paragon’s Graphite spyware to a surprising target list in Italy—not just journalists and activists, but powerful businessmen such as Francesco Gaetano Caltagirone and potentially Unicredit CEO Andrea Orcel. What began as a tip over coffee became months of reporting: corroborating confidential leads, aligning Apple and Meta state-sponsored attack alerts, and reconstructing how zero-click exploits likely reached devices. With reluctant sources and official silence, Angius shows how opaque procurement and potent surveillance tech collide—raising hard questions about accountability, national security, and the public’s right to know.

How did you first discover that high-profile individuals, including Francesco Gaetano Caltagirone, were targeted by Paragon spyware? What prompted IrpiMedia and La Stampa to verify targets beyond activists and journalists?

As with the best investigations, it all began with a source — and a conversation over coffee. At first, the story was mainly about Caltagirone and the likelihood that he had received a compromise notification. What followed were long trips across Italy and abroad, where I met other sources and people who might hold small but crucial pieces of information. It turned into a long piece of work, stretching from May to October, but by summer the picture was already coming into focus. That’s when it became possible to identify a cluster of businessmen targeted by espionage — and when the possibility emerged that the CEO of Unicredit might also be among them.

What investigative steps did you and your team take to confirm the delivery and nature of the spyware? How was the WhatsApp “zero-click” attack method identified and validated in this case?

The main issue with anything related to Paragon spyware is that we can’t actually tell whether an attack was successful — only whether the manufacturers of the targeted technology (WhatsApp or Apple, in the case of iPhones) detected signs of a possible attack against you. The methods these companies use to identify potential targets aren’t entirely transparent, but one thing is certain: if you receive a notification from them saying you “may have been the target of a state-sponsored attack,” then someone, at some point, at least tried to spy on you.

In our case, things were even more complicated than in attacks against journalists or activists, because — unlike them — our targets likely didn’t want the story to come out. That meant we didn’t have their cooperation. All we could do was verify and cross-check our sources and the technical details they provided.

Can you explain the collaboration process with other journalists, activists, and organizations like Citizen Lab? How did forensic device analysis contribute to piecing together the attack methods and timeline?

For this investigation, we didn’t have the support of Citizen Lab or other organizations that focus exclusively on protecting journalists and activists. The main figures in our story are businessmen — some of the most prominent in Italy. They would never have turned to organizations that are, in one way or another, part of the activist world.

That said, we learned a great deal from Citizen Lab and Access Now, especially through the technical analyses they publish on their websites. And a few people close to those organizations helped us on a personal basis — under strict anonymity — to understand, from a technical standpoint, exactly what we were dealing with.

Were there any significant challenges in obtaining confirmations from victims, their press offices, or technical experts? How did the lack of response from certain parties, such as Caltagirone’s team or Paragon Solutions, impact your investigation?

The silence of the victims — Caltagirone and Orcel — was a serious challenge in the run-up to publishing the investigation. Personally, I’m meticulous to the point of obsession, and I would have really liked to have a technical exchange with them — by then, they already knew we were going to publish. We went ahead without it; it’s part of the game. But the absolute silence that followed the release of the story ended up being, in a way, a confirmation from their side: we had gotten it right, and they couldn’t refute it.

What role did public alerts from Meta (WhatsApp/Facebook) and Apple play in tracking the spread of the spyware? How did you verify and reconstruct events after these notifications were sent?

In both Caltagirone’s and Orcel’s cases, we were able to determine the exact time and date of the notifications they received. Once that was confirmed, it was easy to connect the dots: other victims had received the same round of notifications, and later, Graphite — the spyware developed by Paragon — was found on their devices. In this sense, those notifications were crucial; they’re the backbone of our investigation.

I know that, both in Italy and across Europe, there’s been some debate about whether companies should be allowed to notify users of potential compromises. But that’s like asking an antivirus program not to alert you when it detects malware on your computer. These notifications are essential — they’ve made it possible, time and again, to uncover cases in which authoritarian regimes have abused surveillance technologies.

The same notification received by Caltagirone and Orcel was also sent to two journalists, Ciro Pellegrino and Francesco Cancellato. The government has always denied spying on them, yet it doesn’t seem particularly interested in finding out who did. Instead, the priority appears to be stopping the notifications themselves. In short, we’re pointing at the Moon — and they’re trying to cut off the finger.

How did you navigate and corroborate conflicting information from government responses and intelligence agency reports versus independent forensic findings? What strategies helped cross-check rumors of foreign versus domestic involvement?

As I mentioned, in the case of the journalists the government denied any involvement, while in the cases of Caltagirone and Orcel there’s still been no official statement — as of October 29, nearly three weeks after the publication of our investigation. In the past, there’s even been talk of possible foreign attacks against Italian journalists, which sounds rather peculiar. But even if that were true, shouldn’t it be the government itself demanding explanations and insisting on answers if a foreign country were conducting offensive cyber operations against Italian citizens? That’s exactly what we keep asking — yet so far, all we’ve received is silence. And that silence only fuels further suspicion.

Could you elaborate on how you balanced the technical complexity of “zero-click” exploits and the need for clear storytelling for your audience?

I’ve always thought of myself as a kind of “correspondent” in the cyber world. Just as some colleagues specialize in a particular country — writing about it daily and translating its complexities for their readers — I like to think my “beat” is the digital realm itself: a place made up of companies, state actors, hackers, and whistleblowers.

It’s probably through listening to all these different people, and trying to get these worlds to speak to one another, that I’ve developed a taste for telling complex stories in a way that anyone can understand. In the case of spyware attacks, that’s paradoxically easier: everyone can grasp the difference between an attack that happens when you click a link and one that happens almost magically, without the victim ever realizing it.

What really interests me, though, is helping readers understand the economic logic behind it all: every one of us is a potential target of some kind of attack. But these attacks vary in cost and in the effort they require — and that, to me, is a simple but accurate way to explain this world. Whether I’m always successful at it, though, is something you’d have to ask my readers.

Were there ethical dilemmas when reporting on surveillance victims who preferred anonymity, or when handling sensitive findings about spyware contracts and cost estimates?

Contracts and costs — in this world as in any other — are what truly define the boundaries of cybersecurity. Not only do I have no problem writing about it in those terms, but I actually believe governments should be far more transparent on the matter. Paradoxically, it’s often easier to find out how much we spend on weapons than how much we spend on surveillance technologies. The difference, of course, is that in a democracy, weapons are rarely aimed at one’s own citizens — whereas surveillance is a fluid kind of weapon, one that expands its reach as it becomes more affordable.

We’re moving steadily toward a state of total control, and we don’t even know how much it’s costing us. If we did, activists and journalists would have one more tool to describe — and perhaps to challenge — the consequences of the growing security turn in our societies.

As for revealing the victims’ names — even against what we believe might be their wishes (they never actually asked us not to publish, when we contacted them before the story came out) — I think it’s perfectly reasonable, given the context. We’re talking about one of Italy’s most influential businessmen, who happens to be close to the current government, and the CEO of the country’s second-largest bank. The potential compromise of their devices is, in every respect, a matter of national security. Our job is to report it — while, of course, giving the individuals concerned the opportunity to comment, should they wish to do so.

What lessons did you learn about the broader surveillance industry and government contracts while investigating Paragon and Graphite? How does this case reshape your approach to future reporting on cyber surveillance and digital threats?

One lesson I’ve certainly learned is that there’s simply no scenario in which accountability and surveillance can truly coexist. It’s inevitable that certain tools will proliferate, expanding to fill every available space like a gas. Meanwhile, there are very few mechanisms capable of assuring citizens that such tools won’t be abused.

Since we don’t know who spied on Caltagirone and Orcel, I can’t determine whether there was any legitimate basis for such surveillance against two of the most prominent and influential figures in the country. But even if it were legitimate, that would make it even more troubling — because the same tools have been used against fellow journalists, without anyone in government helping to uncover who might have targeted them.

Our societies rest on a social contract: if a government cannot even answer these kinds of questions, it shouldn’t be allowed to use tools so invasive and harmful to the private lives of its citizens.